Will Japan’s remilitarisation drag us into a war?

Tectonic shifts are underway in Japan that further confirm how much and how fast our world is changing. Recently announced Japanese rearmament will place a heavily-armed and nationalistic Japan on a potential collision course with China. What is driving this? Is Japan acting in concert with the US to contain and ultimately confront China – or are we witnessing a Japan that is emerging from US occupation? Should Australia and New Zealand welcome or fear Japanese rearmament?

Australia and New Zealand paid scant attention to the 8 February snap election that handed Japan’s ‘Iron Lady’ Sanae Takaichi (LDP party) and her allies the super-majority needed to complete the nationalist agenda of turning Japan back into a major regional military force capable of projecting power. It will spell the end of the pacifist Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution – the cornerstone of foreign policy since 1947 – and could bring us closer to a devastating regional war.

Soon after taking office late last year, Takaichi announced Japan would move rapidly to increase defence spending in its five year plan to 2% of GDP from 2027, a massive hike from the traditional 1%, given Japan is the world’s fourth largest economy. Japan may soon leap up the global rankings for defence spending from its current 10th place to number three.

Upon assuming the premiership last year, Takaichi immediately provoked China by saying Japan would view any move on Taiwan as a "survival-threatening situation" (sonritsu kiki jitai). This was seen by regional scholars as a deliberate code reference to the framing of Japan’s occupation of Taiwan and Manchuria in WWII.

At the same time, Japan ratcheted up the tension by moving missile systems to Yonaguni Island, just 110 kilometers (68 miles) from Taiwan. It has also restored WWII titles for military ranks which, according to the South China Morning Post is “a symbolic gesture to please conservatives … and could stoke regional tensions.”

Is Japan acting as a US vassal or an emerging regional power?

Some critics of both the US and the current Japanese government say Japan is actually acting as a vassal to the US, joining in a belligerent confrontation that will end in tears. Certainly, this narrative fits neatly with the US National Security Strategy launched last year in which the US makes clear that there will be a division of labour and an expectation that allies must shoulder a heavier burden.

In line with this tendency, New Zealand has doubled defence spending whilst Australia, as part of AUKUS, has already committed $386 billion to what many consider an ill-conceived project to build a fleet of nuclear attack submarines designed to operate in the South China Sea.

Feeding into the ‘Japan is acting as a vassal’ argument, the increase in funding was welcomed by Washington-based defense think tanks. In an article titled “Japan’s New Defense Budget Is Still Not Enough” Jennifer Kavanagh wrote on the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace site:

“This will give the country the third-largest defense budget in the world,” but, “Washington will need to keep the pressure on Tokyo to stick to and even expand its defense investment further – for example, by making U.S. military assistance to Japan conditional on continued, larger increases in Japan’s defense spending in coming years,” Kavanagh said.

In contrast, Professor Robert Patman of Otago University, one of New Zealand’s leading geopolitical analysts, sees Japan reacting to changed geopolitical realities.

“The Japanese desire to have a greater military capability reflects the fact that Japan feels it can't rely on the United States in the way that it could in the past. Japan has been very clear-eyed about the current Trump administration in a way that our government has struggled to be.”

“There is a perception that Japan may be inviting trouble if it does not signal that it was prepared to invest more than previously in the military sector,” Professor Patman told me this week. “In other words, I think Japan feels that it's more likely to have a constructive relationship with China if it's perceived to be realistic about its own military capabilities.”

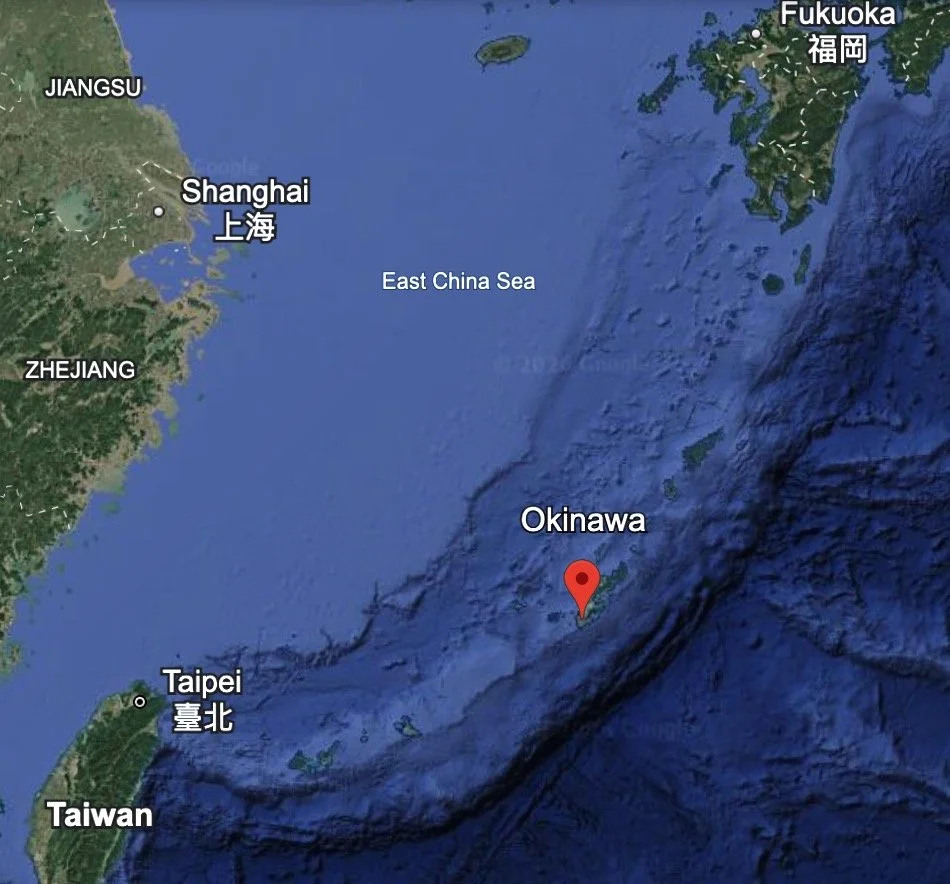

Image: Map data ©2026 Google

The East China Sea is the site of intense security competition. The Japanese, emulating the Americans and the Chinese, have deployed what Professor David Vine calls a Lily Pad strategy, planting a chain of military bases on what are in many instances little more than rocks in the sea in order to dominate a body of water and the resources beneath. Vietnam, the Philippines and others are doing the same in their contested waters.

Japan has genuine concerns, not least the Bashi Strait between Taiwan and the Philippines, a narrow chokepoint through which much of its trade passes. And one mustn’t forget the long running contest over the Senkaku Islands.

When elephants fight, the grass gets trampled

The risks these moves collectively pose are many for the lesser regional players like Australia and New Zealand. They signal that the “rules-based order” – or the better concept of international law in accordance with the UN Charter – continues to be weakened by hard power realism.

Mike Smith from the Wellington-based peace group Just Defence says New Zealanders should fear not welcome Japanese militarisation.

“When elephants fight, the grass gets trampled,” Smith told me. “We should stay out of the grass and yet we are being pulled into these arrangements like NATO’s IP4 – Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea.”

Image: Map data ©2026 Google

He was speaking at the very moment New Zealand Defence Minister Judith Collins was at the Munich Security Conference. Collins, as well as meeting NATO secretary-general Mark Rutte, will speak at a session on the interconnected nature of security challenges in the Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic regions.

Long-standing cross-party consensus on defence and alliances is breaking down in New Zealand. The opposition parties are signalling a determination to move New Zealand back to a more independent stance on foreign policy.

“We should be concerned about Japanese militarisation and also about the encroachment of NATO into our region,” Smith said. “We should avoid being pulled into other people's fights. If the current Japanese government wants to take on China, this is not a fight that we should be looking to join. The agendas that countries like Japan have are not our agendas. The concerns we have about our role in the Pacific are not their concerns.”

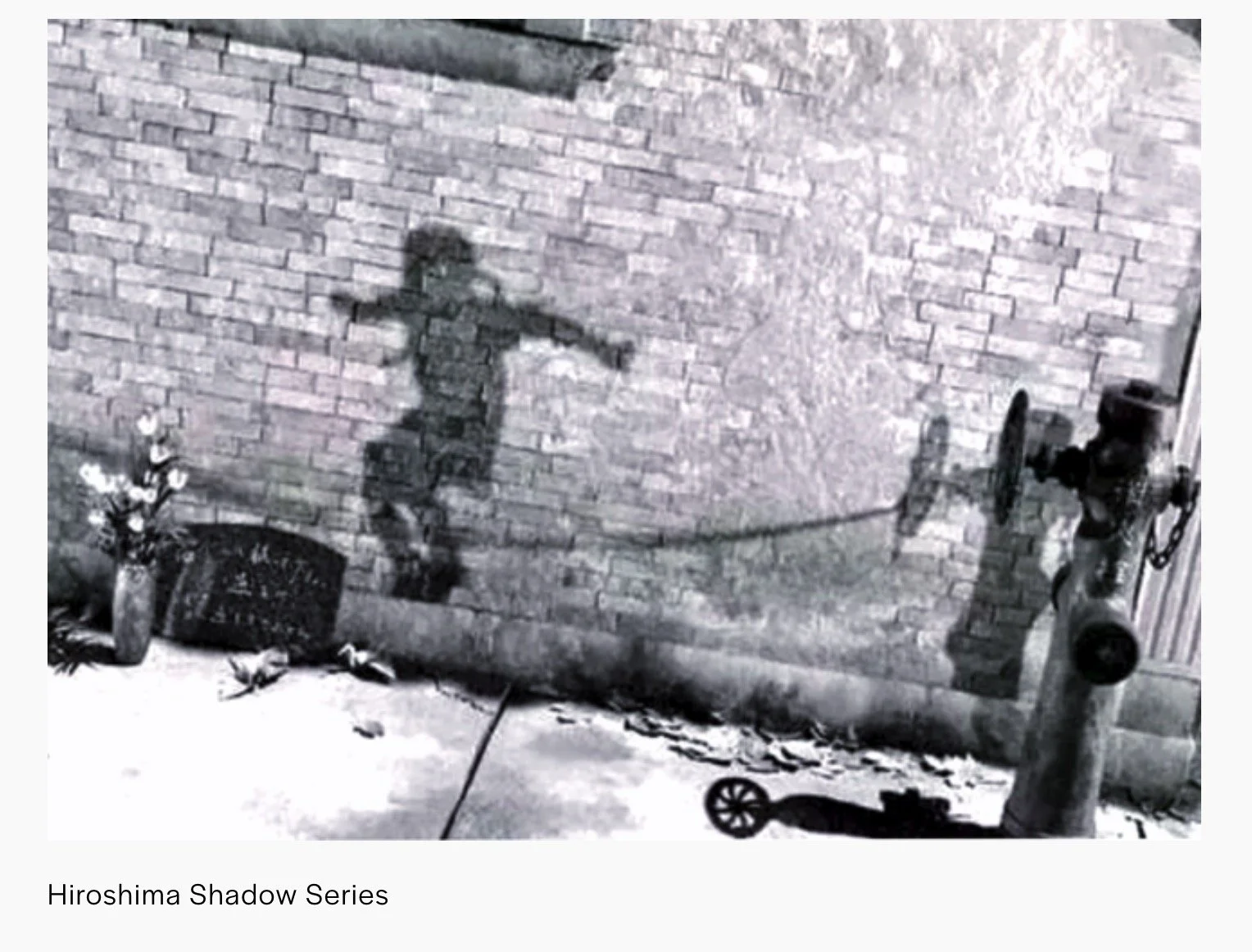

Japanese politicians are openly discussing going nuclear

Rearmament can make you strong but it can also, as history has shown, lead to war. There is a real risk that turning Japan into a major war-fighting power will create a security dilemma for China and other East Asian powers. In geopolitics a security dilemma is the spiral effect that occurs when one power by increasing its own security almost invariably reduces the security of its rivals. Unintended – or sometimes intended – consequences follow in terms of arms races, hair-trigger tension, and actual confrontation. Nuclear proliferation is a major risk. It would be sad and ironic if Japan, the only country to have experienced a nuclear attack, decided to become a nuclear weapons state. The hawks inside Takaichi’s LDP are openly discussing this option.

In December the influential Asahi Shimbun paper reported: “Japan should possess nuclear weapons, given the severe surrounding security environment and the questionable reliability of the U.S. nuclear deterrent, an official who advises Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on security policy said.”

So here we are. Should New Zealand and Australia keep off the grass, choose an elephant or tip-toe between them? Yes, we want more trade with Japan. Yes, we want more trade with China. Yes, we want to avoid the sanctions that come with the Wrath of Trump. But. America is not our friend. China is not our enemy. And Japan must now be added to the growing list of countries that should concern us.

Eugene Doyle

Eugene Doyle is a writer based in Wellington. He has written extensively on European geopolitics, Middle East, and peace and security issues in the Asia Pacific region. He hosts the public policy platform solidarity.co.nz.

This article may be reproduced without permission but with suitable attribution.